The analysis of handcraft metal technology cannot ignore the identification of metal supply sources and the analysis of the tools used for the long manufacturing process.

The difficulty in identifying clear archaeological evidence of metal working, thus not only related to the presence of kilns which could have also been used for other functions (e.g. the firing of ceramics), led to the establishment of some criteria for the identification of metal transformation areas such as the presence of ovens set up for a ventilation system; the discovery of tools such as crucibles, casting moulds, and the possible presence of slag.

The main regions from which the metal came were adjacent to Mesopotamia and Syria; the Zagros mountains, the Iranian plateau, Magan, where most of the copper came from, and Central Asia which probably exported tin.

The excavation of the Norşun Tepe site, in the Keban area, south-western Anatolia, brought to light archaeological traces, attributable to the end of the 4th millennium BC, relating to different phases of metal processing (slag, minerals, furnaces). The metal ore used was probably originating from the Ergani Maden mine, one of the few sites from which it comes the analysed waste dating back to the mid-4th millennium BC. Slag analyses have been carried out in Oman’s mining areas since the 1980s.

Of notable importance was the discovery of the Göltepe site (Ancient Bronze I) and the Kestel mine in the central Taurus mountains in Turkey in the 1990s, which made it possible to recognize large deposits of tin. The investigations conducted highlighted the presence of a vast mining district associated with a settlement of underground homes where metallurgical installations were found with evidence relating to the smelting of tin. The extension of the area of activity in which the mine operations, the processing in the surrounding areas and the related industry were carried out, must have been approx. 60 hectares. Hundreds of crucibles ranging in size from 0.20 to 0.50 m and pits for metal slag were found within the settlement in Area E. Also in areas A and B, various artefacts were found such as mortars and pestles used to break the ore, stone millstones and axes and a large number of multiple open casting moulds in kaolinite with engraved regular bar matrices. The shape suggests the production of easily transportable and marketable tin ingots.

In the Wadi Arabah region, in particular in the mining districts of Timna, in the western part, and Faynan, on the eastern edges of the Wadi, there is the presence of important copper deposits, which appear to be the largest in the southern Levant. Some evidence from Faynan, and rare evidence from Timna, is related to mining activities and metal production dating back to the Early Bronze Age.

Activities in Timna are documented for the Late Bronze Age, while both of the above-mentioned areas are affected for the Iron Age. The technological similarities between Faynan and Timna demonstrate an intense exchange between the two mining districts (shafts, tunnels, chambers and pillar constructions, slag, location and type of smelting furnaces). Copper from Timna was exported to settlements near Aqaba, and probably from here to the Nile Delta; copper from Faynan was exported to settlements in the Beersheba Basin from the Late Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Metals from the Jordan Valley and the northern part of the so-called Levantine corridor were also used, in addition to local ones.

One of the clearest indicators of metal trade are ingots, which are difficult to find in context and of which different types can be recognised. In some cases the discovery of casting moulds for the production of ingots are the only evidence for their production.

In Oman, some circular (bun-shaped) copper ingots dating back from the second half of the 3rd to the 1st century of the 2nd millennium BC were found, which must have been used in long-distance trade towards southern Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf and the Indus River Valley. Of the same typology are five specimens from Susa, dating to the mid-3rd millennium BC, and associated with two specimens from Tell Chuera, and those identified in some settlements in the Indus valley and the Gulf.

At Tell Sifr a disk-shaped copper ingot was part of a deposit of early Babylonian agricultural equipment while of the same type is a large flat-convex ingot, now preserved in the British Museum, of unknown provenance.

The plano-convex shaped ingot is known in Neo-Assyrian workshops, as confirmed by the specimen from Nimrud, and, in more archaic contexts, in Maysar, where a deposit with some fragments was found of copper ingots near a small furnace. This confirms the relations between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC.

The bar-ingot typology characterises the 2nd millennium BC; some were found in the workshops of Tell el-Dab’à, the ancient Avaris in the eastern part of the Nile delta, where they were probably produced, others were found in the Giparu in Ur.

In the texts of the Ebla archives, precious metal ingots are often mentioned.

The probably best known ingots are of the “ox-hide” (ox-hide or peau-de-boeuf) type, widespread in eastern Anatolia, Syria, Iraq, Cyprus, Egypt in the Nile Delta, Crete, in mainland Greece, Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica.

They are characteristic of long-distance Mediterranean trade starting from the 2nd millennium BC, with particular diffusion during the Late Bronze Age.

At Ras Ibn Hani a casting mould of this typology was found in a palace laboratory; similarly, an ingot dated to the 12th century BC comes from level I of Agar Quf.

The so-called “oxhide” ingot has often been represented as being on the base of Shalmaneser III’s throne in Nimrud and, always associated with tributes to be paid to Neo-Assyrian rulers, on the Rassam Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal II.

An important corpus of 354 copper ingots was found in the Ulu Burun wreck located on the Turkish coast, south-east of Kos, approximately 45 m deep, dated approx. to 1300 BC. Of these ingots, 317 have the typical “oxhide” shape, 31 ingots are characterized by two protuberances, both on the same side, while another 6 ingots were smaller in size (of these, 4 are almost exactly identical, probably produced with the same casting form).

There are 121 intact ingots of a plano-convex discoidal shape, more rarely they are oval in shape, of the dog biscuit or “flag” type. Some analytical studies have been aimed at understanding the place of origin of the metal, for example the “oxhide” ingots probably come from Cypriot mines while the place of origin of the tin, transported in the form of a rectangular “oxhide” ingot or disk, remains unknown.

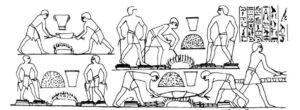

As regards the tools used in metalworking, stone percussion instruments associated with small chisels are also worth mentioning.

Crucibles of different sizes and some univalve casting shapes worked on multiple faces were found in the semi-subterranean or subterranean dwellings/laboratories called “pit-houses”.