The Phoenicians were the first to recognise the great value of Algeria’s mining heritage: Without the enormous human, economic and material resources of Algeria, Carthage would never have become a powerful country, strong enough to stand up to Roman power.

Traces of the exploitation of one of the richest copper mines in ancient Algeria, certainly known in Punic times, have been found at Bou Khandek, in the region of Cartenna (modern Ténès), which, according to S. Gsell (1981, p. 212), corresponds to the Kalkorukeia that Strabo places in the land of the Massesili (Posidonius source of Stradone, XVII, 3, 11). The place name Cartenna may be of Libyan-Berber origin and the town, probably the Kalka of Scylace’s Periplus (110-111) and Polybius’ Kalkeia (XII, 5), situated on a rocky plateau overlooking the mouth of the Oued Allah to the west, must have been the market and storage port for the ore coming from the mining basin to the north-east, south and south-east of the centre. There is no

archaeological evidence of the Punic settlement, except for chamber and pit tombs excavated in the rock, which seem to have yielded late material. On the other hand, Poseidonius (XVII, 3.11) mentions the existence of an asphalt spring in the village of Massesili, probably in Ténès.

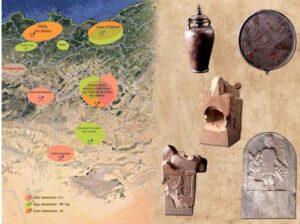

Ancient lead, zinc, iron, and copper mines have been found in the region of Hippo Regius (Annaba), at Kef Oum Téboul; lead and copper mines in the lower Kabilia between ancient Igilgili (Jijel) and Saldae (Béjaïa), in the Setif region and in the Houdna mountains; iron (magnetite and hematite) in the Edough massif (Mokta el-Hadid) and in the Chullu (Collo) region.

Silver and gold have been found mainly as by-products of lead and copper, especially in the deposits of the Cavallo area, where copper workings have been identified, and at Kef Oum Téboul. Mercury has been found in the Azzaba area in Skikda and in Mra Sma, while antimony has been found in Tiddis, Ain Kerma (El-Teref) and in Djebel Taya in Bouhamdane (Guelma). Recognised for their magical, cosmetic, and antibacterial properties, these two minerals were very important in the manufacture of alloys, since, like arsenic, they lowered the melting point of copper, making it easier to work.

In Algeria, there is no archaeological evidence of workshops from the Punic period, but a stele from the tophet of El-Hofra in Constantine attests to a blacksmith, in Punic nsk, from the root nsk ‘to melt’. Carthaginian epigraphic documentation also records the specification of smelters of gold, iron, bronze, and molten metal. Like the inscriptions, iconographic evidence is scarce and dates to between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC: tools such as tongs, hammers and bellows are represented only on two stelae from the tophet of Carthage.

Mint of Massinissa and successors (206- 148 BC)

It is difficult to say whether the metal objects found in Algerian Punic contexts are of local production. Probably, the iron weapons from Rachgoun and Bethioua and those preserved in the Annaba and Constantine museums are. The bronze amulets preserved in Oran in the Egyptian tradition are probably imported, while the female amulet in the Constantine Museum may be of local manufacture.

The production that can certainly be attributed to local craftsmen is that of coins, which developed from the end of the 3rd century BC in many coastal towns of the Algerian interior and in the kingdoms of Numidia and Mauritania. Of considerable interest is the converging hypothesis of the North African origin of the metal used, which is confirmed by the frequent finds of lead or bronze-coated lead coins in the area between Tabraca (now Tabarka, in Tunisia) and Rusaddir (now Melilla, a Spanish enclave on Moroccan territory), dating back to the reign of Massinissa or Micipsa (late 3rd – second half of the 2nd century BC) and circulating in conjunction with Numidian and Carthaginian bronze series. From Icosium (Algiers) come as many as one hundred and fifty-four lead coins of the 2nd century BC from the local mint associated with Numidian coins.

Neo-Punic coins from North Africa from the 2nd-1st century BC depicting Chusor: a) D/ coin of Lixus; b) R/ coin of Hippo Regius (?); c) D/ coin of Macoma

The small number of specimens subjected to microchemical analysis showed varying amounts of copper and lead and, in general, less pure lead in the Numidian issues than in those from Icosium. This phenomenon has been interpreted because of the Numidian rulers’ inability to cope with the sudden need for money after the fall of Carthage. However, analyses of Annibalic coins from the African mint seem to show that the progressive addition of lead was already consolidated in the Punic period, in line with the gradual transition from the binary alloy of copper and tin to the ternary alloy of copper, lead and tin, which is recorded throughout the western Mediterranean in the Hellenistic and Roman Republican periods.

Of considerable interest is the representation of divine figures on the coins of the Neo-Punic mints of Algeria, which somehow suggest a link with metallurgical activities. The divine figures on the coins of Macoma and Hippo Regius (?) in the Cirta region are characterised by a strongly local iconography and the constant presence of astral symbols, which find an interesting and direct counterpart in the iconography of the Dioscuri on the coins of Utica (?) from the 2nd century BC, where a star appears both on the obverse and the reverse. They are identified with the Cabiri, goldsmiths and masters of fire, “lords of the furnaces”, in whose mysterious rites the role of metals was important.

The figure appears on Hippo Regius issues. Similarly, the bearded divine figure on the coins of Macoma, wearing a headdress ending in two appendages and interpreted as Chusor-Ptah, has a star behind his neck, which links him to the issues of the

Hippo Regius (?) mint and the uncertain mint of the Constantinian area. The figures, which certainly have a strong local character, thus seem to carry a symbolism linked to magic and metallurgy. At this point, it seems no coincidence that the mints of production are in one of the richest mining areas of North Africa. Macoma, as the name itself suggests (an abbreviation of mqm ḥdš), identifies a ‘new market’ located on the route into the Numidian hinterland between Cirta and Theveste, towards the mining basins closest to Carthage.