The earliest evidence of metalworking in the Phoenician foundations in the Malaca area dates to the 8th century BC, and even in Punic times the area was of strategic importance for the control of the routes leading to the Sierra Morena along the Guadalhorce river. The continuity of mining in these regions is documented, among other things, by the discovery of a Carthaginian coin linked to an Iberian one at a depth of twenty-five metres in a Roman tunnel in the Dehesa de Covatillas mine, in the province of Cordoba. Another important Phoenician centre for silver and copper metallurgy from the 7th century BC is Baria, where the ore from Castulus was probably transported and later exported to Carthage. However, the region most affected by the Phoenician presence remains western Andalusia, with Gades, from the 8th century BC, the pivot of an economic system designed to control the Atlantic slope, the arrival point of the routes from the East, manager of a commercial network that extended from the Tagus estuary to Extremadura and the westernmost part of the Meseta, to the Quadalquivir valley (the Tartessian area and the mining districts of Huelva and Aznalcollar), to Lixus and Mogador in Atlantic Morocco (the silver and iron mines of Djebel Hadid, north-east of Mogador). The mining system, which in Phoenician times was in the hands of local potentates, seems to have come under direct Punic control from the Barcid period onwards. The main centre of the new organisation became Carthago Nova although the end of the 3rd century BC saw the strengthening or creation of Punic or Punic centres in most of the known mining areas. The Punic presence is attested in the Oretan region at Akra Leuke and Castulo, in the Mastic and Bastetan region at Carthago Nova, Baria, Tagilit and Alba, in the Bastula region at Malaca, in the Turdetan region at Ituci and in the Beturia Turdula at Hornachueolos.

The south of Portugal is also important in terms of natural resources. In particular, the mining area of Aljustrel (famous from an archaeological point of view for the discovery of the Vipasca site and the Vipasca bronze tablets, known as lex metalli vipascensis, dating from the 2nd century AD). In the Aljustrel area, in addition to the Roman site of Vipasca and the mineral deposits of S. Joao do Deserto, Algares and Moinho, Neves Corvo and Ourique have also been identified.

The area around the Rio Guadiana is particularly rich in mineral deposits belonging to the Iberian pyrite belt and is dotted with archaeological sites where the Phoenician presence is well documented. In particular, the mines of Monte Judeo and Gomes have been identified as areas of great interest, also due to their proximity to archaeological sites with documented occurrences since prehistoric times, such as that of Alcoutim. Ancient mining activities are also documented at the Cova dos Mouros archaeological site, as well as the Sao Domingos mine, which is still active today. The areas of Almada de Ouro, a mining site where the Romans carried out gold mining, have also been identified, as well as Castro Marim in the Algarve, a Phoenician centre at the mouth of the Guadiana.

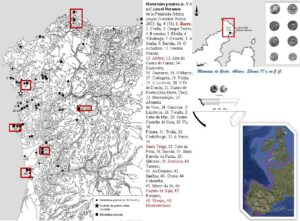

The Atlantic route inevitably touched Portugal, where recent archaeological research has documented the presence of Phoenician settlements all along the coast and in northern Spain. Among the most interesting finds are coins from Cádiz, Abdera and Ebusus, which were found in the port of Bares in Galicia. The cape close to this site is called Punta da Muller Mariňa, which, according to A. González-Ruibal, could be identified with the Cape of Venus mentioned in the extreme north of Iberia, in the periplo of Imilcon, as already hypothesised by E. Aubet (Avieno, Ora Maritima, 158).